As a child I dreamed of being a bass clef singer. My first operatic ‘crushes’ were the D’Oyly Carte bass Donald Adams, the Dutch singer Arnold van Mill (whose LPs I collected) and Tito Gobbi (who I saw in Tosca and Otello at Covent Garden before my twelfth birthday). It was only after I arrived in London that I became familiar with the magnificent voice of Lawrence Tibbett.

Thanks to his film appearances, Tibbett was one of the first American home-grown classical singers to become famous outside his country, although his appearances outside the USA were infrequent. His father, deputy sheriff of Bakersfield in California, was killed in a shoot-out with outlaws when Lawrence was a child and his mother moved the family to Los Angeles. Young Lawrence (Larry) developed an interest first in acting and then in singing and in 1922 he moved to New York, leaving his wife and young family behind until the money could be raised to join him. Tibbett took singing lessons with Frank la Forge and made his Met debut in 1923 in a small role in Boris Godunov.

At first he had to be content with comprimario roles but his break came in early 1925 when he sang Ford in Falstaff. As the very junior member of a star-studded cast (Scotti, Gigli, Bori, Alda, Telva were also singing), Tibbett was firmly put in his place during rehearsals but come opening night they, Maestro Serafin in the pit, and the audience were firmly aware that a new star had arrived: Tibbett was given a sixteen minute standing ovation.

But the Met did not oblige immediately with meaty roles and for the next two seasons Tibbett had to be content with offering audiences snippets of his future repertoire during concert recitals and making recordings, the first of which was for RCA Victor in 1926 (Pagliacci Prologue).

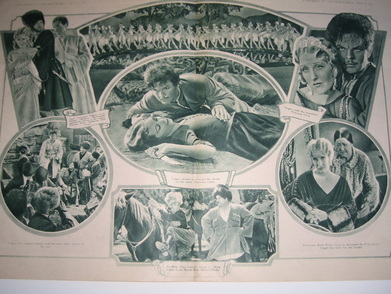

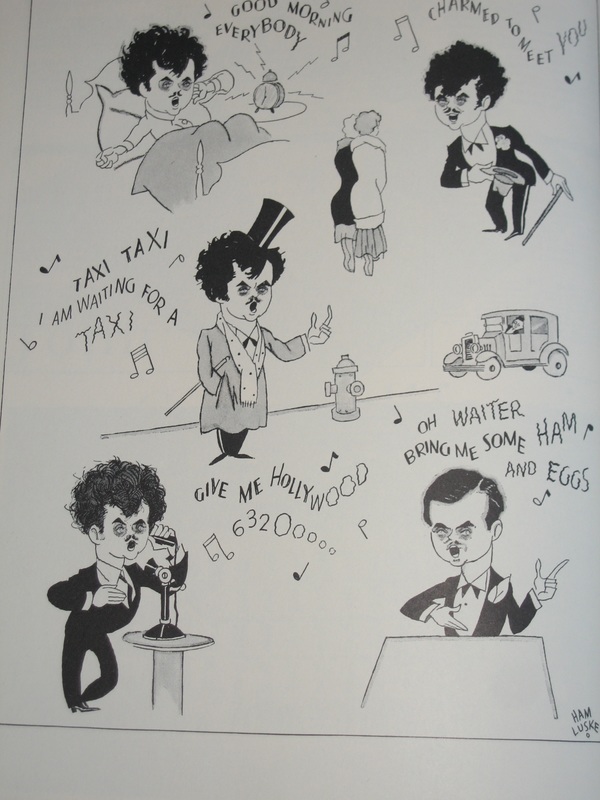

Sound film was in its infancy when the six foot two, athletically-built Tibbett received the call from MGM in early 1929 to star in The Rogue Song (based on Lehár’s Gypsy Love with additional songs by Herbert Stothart, directed by Lionel Barrymore and co-starring Catherine Dale Owen and Laurel & Hardy). The film – the first musical filmed in colour – was a smash hit but sadly is now lost.

Thanks to his film appearances, Tibbett was one of the first American home-grown classical singers to become famous outside his country, although his appearances outside the USA were infrequent. His father, deputy sheriff of Bakersfield in California, was killed in a shoot-out with outlaws when Lawrence was a child and his mother moved the family to Los Angeles. Young Lawrence (Larry) developed an interest first in acting and then in singing and in 1922 he moved to New York, leaving his wife and young family behind until the money could be raised to join him. Tibbett took singing lessons with Frank la Forge and made his Met debut in 1923 in a small role in Boris Godunov.

At first he had to be content with comprimario roles but his break came in early 1925 when he sang Ford in Falstaff. As the very junior member of a star-studded cast (Scotti, Gigli, Bori, Alda, Telva were also singing), Tibbett was firmly put in his place during rehearsals but come opening night they, Maestro Serafin in the pit, and the audience were firmly aware that a new star had arrived: Tibbett was given a sixteen minute standing ovation.

But the Met did not oblige immediately with meaty roles and for the next two seasons Tibbett had to be content with offering audiences snippets of his future repertoire during concert recitals and making recordings, the first of which was for RCA Victor in 1926 (Pagliacci Prologue).

Sound film was in its infancy when the six foot two, athletically-built Tibbett received the call from MGM in early 1929 to star in The Rogue Song (based on Lehár’s Gypsy Love with additional songs by Herbert Stothart, directed by Lionel Barrymore and co-starring Catherine Dale Owen and Laurel & Hardy). The film – the first musical filmed in colour – was a smash hit but sadly is now lost.

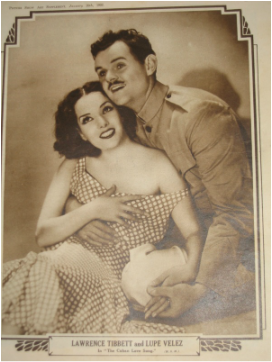

| Tibbett’s recordings of “The White Dove” and “When I’m Looking At You” were best-sellers and by the time of his second film (The New Moon with Grace Moore and Adolphe Menjou) he was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars. Tibbett continued to make film musicals into the mid 1930s often playing opposite glamorous ladies such as Lupe Velez but public taste for big voices on screen waned quickly in favour of more entertaining fare provided by Busby Berkeley and Astaire & Rogers. |

At the Met however it was a different story: throughout the 1930s Tibbett remained hugely popular – live broadcasts of his Germont père (Traviata) (with two other home-grown American singers Rosa Ponselle and Frederick Jagel - available in our next catalogue GEMM 235/6), Simon Boccanegra (alongside Elisabeth Rethberg, Giovanni Martinelli, Ezio Pinza and the young Leonard Warren) and Iago (Otello with Rethberg and Martinelli) have become the stuff of legend, hugely admired even by those who normally listen only to modern recordings. Another magnificent interpretation but rarely heard nowadays in PC-conscious times is that of Erich Gruenberg’s Emperor Jones, (one of several modern roles Tibbett undertook) based on Eugene O’Neill’s powerful drama.

However the voice did not last and recordings from the early 1940s onwards show considerable deterioration to that inimitable, darkly resonant sound. Of many reasons for this decline, one stands out: Tibbett was given to fast-living. An inveterate womaniser and party-goer, he came out second-best in a messy

However the voice did not last and recordings from the early 1940s onwards show considerable deterioration to that inimitable, darkly resonant sound. Of many reasons for this decline, one stands out: Tibbett was given to fast-living. An inveterate womaniser and party-goer, he came out second-best in a messy

divorce and his taste for alcohol, picked up during the Prohibition era, soon became an obsession and then an embarrassment. His second marriage (from 1932) was less fraught but he was unable to resist the many demands that his socialite wife made upon his time; instead of resting after performances he would arrive home to find a party in full swing. It is also thought that Tibbett caused irreparable damage by continuing to sing whilst suffering from a severe sore throat after catching cold during an outside concert. In 1954, not long after a glittering event celebrating Tibbett’s thirtieth anniversary with the Metropolitan Opera, his car was written off following a collision with a pick-up truck and he was arrested for drink-driving. From that moment his life slid further downhill and he looked considerably older than his sixty-four years by the time of his death in 1960.

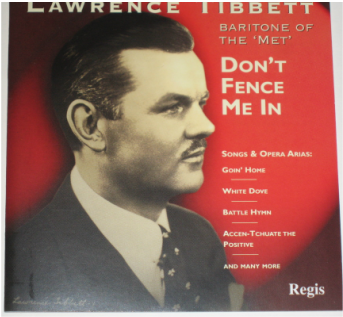

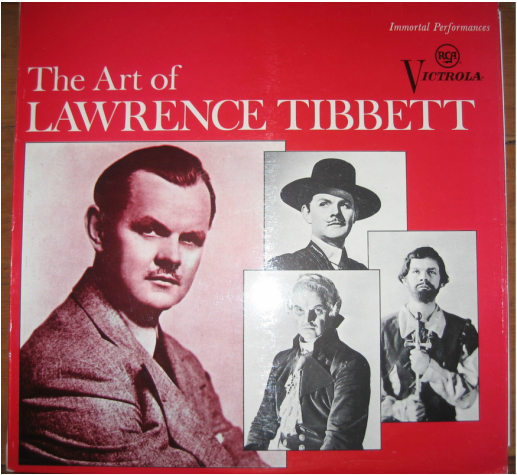

Tibbett’s recorded legacy is highly impressive: the early recordings for RCA Victor of popular operatic arias from Pagliacci, Barber of Seville, Carmen, Tosca, Ballo in maschera etc positively leap from the grooves as do his recordings of Russian and German songs (available from our catalogue VICS 1340). All live recordings are worth investigating for their sheer weight of sound, nuance and acting insights (for relaxation Shakespeare was his preferred reading), even those recorded after his voice had lost its bloom such as his anguished Golaud Pelléas et Mélisande (1944) and his terrifying Michele in Tabarro (1946). The film songs are a delight as are his off-the-air pop songs such as Cole Porter’s “Don’t Fence Me In” and Harold Arlen’s “Accentuate The Positive” both of which he often sang on radio. George Gershwin stated that his ideal Porgy would be a ‘black Larry Tibbett’ and thankfully there are recordings not only of Tibbett performing Porgy’s music but that of Crown and other characters. It’s a voice that comes along once in a blue moon. The blue moon has yet to reappear.

© 2016 James Murray

Tibbett’s recorded legacy is highly impressive: the early recordings for RCA Victor of popular operatic arias from Pagliacci, Barber of Seville, Carmen, Tosca, Ballo in maschera etc positively leap from the grooves as do his recordings of Russian and German songs (available from our catalogue VICS 1340). All live recordings are worth investigating for their sheer weight of sound, nuance and acting insights (for relaxation Shakespeare was his preferred reading), even those recorded after his voice had lost its bloom such as his anguished Golaud Pelléas et Mélisande (1944) and his terrifying Michele in Tabarro (1946). The film songs are a delight as are his off-the-air pop songs such as Cole Porter’s “Don’t Fence Me In” and Harold Arlen’s “Accentuate The Positive” both of which he often sang on radio. George Gershwin stated that his ideal Porgy would be a ‘black Larry Tibbett’ and thankfully there are recordings not only of Tibbett performing Porgy’s music but that of Crown and other characters. It’s a voice that comes along once in a blue moon. The blue moon has yet to reappear.

© 2016 James Murray

RSS Feed

RSS Feed